The H.E.A.T. Collective was founded by Artistic Director Jessica Litwak to create, advocate and inspire artistic expression rooted in healing, education, activism, and theatre. We work to build collectives in every context: in our performances, workshops and community events. Engaging artists across the world, we aim for powerful bridge building art of courageous generosity. In this series, guest experts will write a piece representing each letter of H.E.A.T. - week one will be healing, week two is education, week three is activism, and the last week of the month is theatre. Together these pieces will highlight the work that is being done across all aspects of The H.E.A.T. Collective in the hopes that we can ignite dialogue, spark further exploration, and encourage more people to get involved.

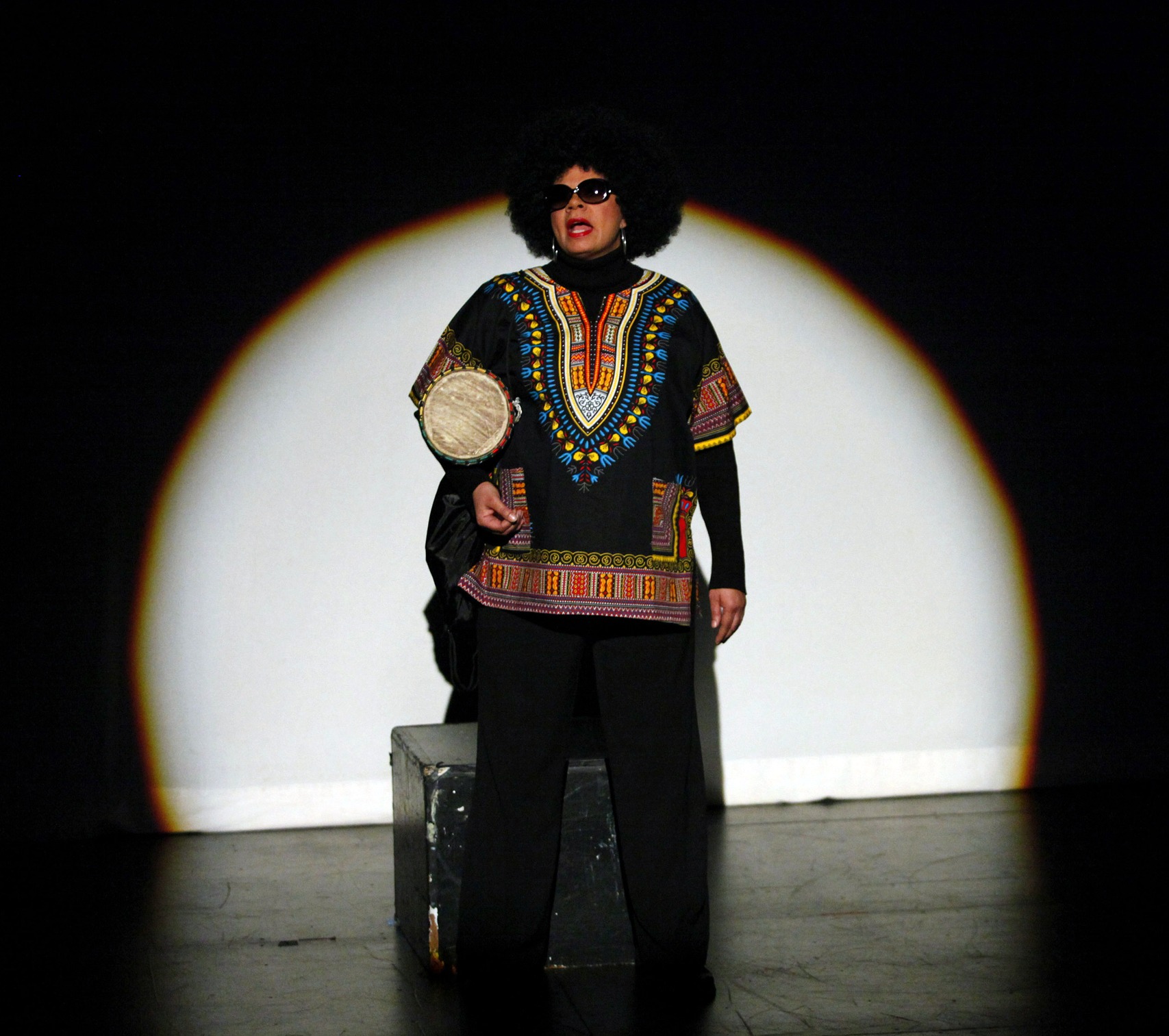

Yvette Heyliger performs an excerpt of Bridge to Baraka in Tribeca Performing Arts Center's Writer's in Performance (2011).

Photo Credit: Kena Betancur

A Match Made in America

A Solo Artist and Her Director

I am primarily a playwright and producing artist. I even directed, but I started out in show business as an actor. After many years on the other side of the footlights, I began work on my first one woman show in 2010 in a performance artist workshop and have been expanding and working on it ever since. Bridge to Baraka is about my coming-of-age artistically, racially, and politically as an advocate for women in theatre, after discovering the Black Arts Movement as an adult.

It is no secret that women theatre artists get less than 20% of production opportunities nationwide. Women of color get even less than half of that, and often experience at a greater intensity being undervalued and underfunded. I started to wonder, in the face of the ongoing plight of women in the American Theatre, what the heck keeps me, an African American playwright, going? What keeps me trying to make a life in the theatre?

When I learned about the Black Arts Movement, a movement that empowered artists to write for themselves, by themselves and about themselves and to get those stories to the masses by any means necessary, I realized that I was standing on the shoulders of artistic warriors. This knowledge was life changing, giving me a renewed strength, resolve, and desire to share the gift of this unlikely movement through the vehicle of solo performance. I realized I had stumbled on to something that mattered and speaks to the times we are living in where women’s issues are in the forefront of American politics.

The opportunity to be back on the other side of the footlights performing a one-woman show that I had written was a challenge. Even with only one solo show under my belt, it has become clear to me that collaboration in solo performance work is a special animal. There are many ways to approach it. Some solo performers write their show and hand it over to the director to direct as they see fit. Others come to the table not only having written the piece, but with their own directing ideas and their own vision as playwrights for the work. They know what they want and are pretty much only looking for a third eye to keep them on course. My collaborative relationship with directors falls somewhere in the middle, perhaps leaning more towards the latter.

It is true, I do have my own ideas and vision for the piece, but I also feel I would be remiss to close myself off to whatever directorial inspiration a director may have, as well as whatever inspiration may result from our collaboration together. With each production opportunity, the work is growing and standing on the shoulders of work that has come before, with a living theatre artist as part of the package! It is important to find a director who is not threatened by this.

The director and solo artist must have mutual respect for one another as theatre artists and as fellow human beings. This is a deal-breaker for me as a first-time solo artist who is returning to the stage as an actor after many years as a writer/director. I found such a director in longtime friend and collaborator, Mario Giacalone.

I first started working with Giacalone on Bridge to Baraka during the BMCC Tribeca Performing Arts’ Writer’s in Performance program in 2011. In this annual program, he leads a diverse group of writers and actors of varying levels experience through a series of exercises culminating in a performance of original work. Bridge to Baraka was still in its early stages of development at that time. Being able to work on the text in front of an audience through the Writers in Performance program was a great opportunity. I was beginning to re-gain my confidence on the stage, not as an actor, but as a writer performing her own work.

The material is challenging and emotional. It is the journey of my life, so I guess that is to be expected. But I found balance and perspective in Giacolone’s approach to the material. He didn’t have a dog in the fight. He was just there to serve the material and to serve the artist—guiding, shaping, and offering ideas along the way. I felt his support and an absolute dedication to helping the artist (in this case me) realize her hopes and dreams for the piece in the theatrical marketplace.

When Bridge to Baraka was selected for the United Solo, the world’s largest solo theatre festival, and played on Theatre Row this past October, I asked Giacalone back to direct the show, which is becoming increasingly feminist in its message. With all the work I have done around parity and creating opportunities for women in the American theatre, Giacalone may seem an unlikely choice. A first-generation Italian from Brooklyn, not only is he male, but he is white! I don’t hold back in speaking my truth, but I am always tuned in to how the show is being received. For this reason, over the years, I have sometimes wondered how Giacalone feels about the journey the play takes and the hot button issues around race that are raised and talked about explicitly in the play.

Unruffled, Giacalone explains, “Fundamentally I believe we are all the same; it’s just the costumes that we wear that are different. Your story has a lot of human qualities to it. Of course it is an African American story, but the kind of relationships and experiences you had with your mom and dad, for example, everybody can relate to. Plus, I came up in the 60’s. I ran with people who were considered the radical left—white people who sold Black Panther newspapers because they believed in the message. You are telling the story of black person’s experience in American during my lifetime and you deliver it in a way that is very pleasing… using humor to make the audience comfortable and able to hear and take in the material and the message”.

The Black Arts Movement reminds us not to take for granted the right to tell our own stories, our own way, and get those plays to the masses. This was not always the case in America for women or for people of color—and unfortunately, as I explained earlier, we still aren’t there yet. We still are in need of opportunities and equal pay once we finally get a seat at the table. It is important to have allies along the way, however unlikely, and Mario Giacalone has been that for me. We are a match made only in America.

Yvette Heyliger and Mario Giacalone after a performance of Bridge to Baraka in the 2018 United Solo Theatre Festival on Theatre Row.

Photo Credit: Dwight Carter

YVETTE HEYLIGER is a playwright, producing artist, educator and activist. She is the recipient of AUDELCO Recognition Award for Excellence in Black Theatre’s August Wilson Playwright Award and Dramatic Production of the Year. She received Best Playwright nomination from NAACP’s Annual Theatre Awards. Author of What a Piece of Work is Man! Full-Length Plays for Leading Women, she has also contributed to various anthologies including, Performer’s Stuff, The Monologue Project, Later Chapters: The Best Scenes and Monologues for Actors over Fifty and 24 Gun Control Plays. Selections from her play, Autobiography of a Homegirl, appear in Smith and Kraus’ The Best Women’s Stage Monologues 2003 and The Best Stage Scenes 2003. Other writings: The Dramatist, Continuum: The Journal of African Diaspora Drama, Theatre and Performance, Black Masks: Spotlight on Black Art, HowlRound, and a blog, The Playwright and The Patron. Heyliger returned to the stage as a solo-artist in her first one-woman show, Bridge to Baraka. From this one woman show came two spin-offs, The Pen Instead of the Gun and I Am That Bear. Memberships: Dramatist Guild, AEA, SDC, AFTRA-SAG and League of Professional Theatre Women. A partner in Twinbiz™, which is celebrating its 30th year, she is the co-recipient of the first National Black Theatre Festival Emerging Producer Award. She has a BA and MA from New York University; an MFA in Creative Writing - Playwriting from Queens College; and a Master of Theatre Education from Hunter College (pending). She was an Obama Fellow (2012) and is a founding member and longtime volunteer with Organizing for Action. As a citizen-artist, she has worked on many issues including: gun violence prevention, equal opportunity and pay for women artists, and most recently, the #MeToo movement. Yvette lives in Harlem, USA.